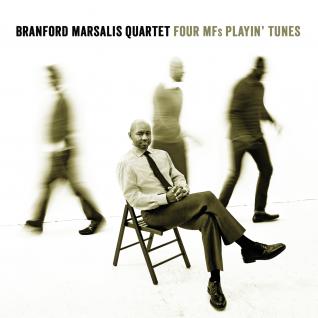

“…the album is a knockout: hard nosed and hyperacute, tradition minded but modern, defined by the high-wire grace of his working band.” -Nate Chinen, New York Times

Legendary saxophonist Branford Marsalis and his tight-knit working band invite audiences into their world of musical cohesion with the release of Four MFs Playin’ Tunes. On this nimble and sparkling album, the band respects the emotional intent of each song and executes that intent with musicianship focused solely on serving the purpose of each tune.

The Branford Marsalis Quartet marks an exciting new era with this record, the band’s first since hiring drummer Justin Faulkner three years ago. There is a decades-long tradition in jazz of young drummers joining established, veteran bands and helping spark the music to a new level. The most famous example occurred in 1963 when seventeen-year-old Tony Williams joined the Miles Davis Quintet, a legendary institution that at the time included Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, and Ron Carter. The young Williams brought an explosive but versatile touch and the band went to a different level. Sometimes a brilliant, still-forming young drummer can ignite fire.

Drummer Justin Faulkner subbed for the Branford Marsalis Quartet’s longtime drummer, Jeff “Tain” Watts, on a one-off gig in 2007 when he was only sixteen years old. When Watts left the quartet in early 2009, after twenty-five remarkable years, he left a hole that not many artists could fill. Faulkner was invited to step in. He was eighteen years old.

The results on Four MFs Playin’ Tunes speak for themselves. Before this recording session, Faulkner and the band had two and a half years of gigs to get to know each other. In October 2011, they walked into the Hayti Heritage Center in Durham, North Carolina, the site of many Marsalis Music recordings in the last few years, and recorded what might be the best album in the Branford Marsalis Quartet’s history. The skill, power, and artistry are the same as always, but Faulkner has injected a lighter, buoyant brand of melodic propulsion to this unit. He’s like an inspired rookie joining a champion basketball team and extending the team’s run of titles by adding eagerness and versatility to go along with serious talent.

The album opens with one of pianist Joey Calderazzo’s impressive originals. “The Mighty Sword” was written for Marsalis on soprano saxophone, and immediately gets the quartet off to a dancing start.

One thing the listener can notice on this first track – a feature that will play out over the rest of the album – is how closely Calderazzo and Faulkner are listening to each other and playing off one another, responding to each other’s nuances. Their communication is so apparent that it gives the quartet a new axis of musical rapport.

The next two tracks are originals by bassist Eric Revis: “Brews,” a quirky, stair-stepping blues with Marsalis on soprano again, followed by “Maestra,” a beautiful mid-tempo tune that Revis and Calderazzo have been playing together recently on trio gigs.

One of the secret weapons of the Branford Marsalis Quartet has always been the composing ability of the leader and the sidemen. Marsalis claims that the band is not a democratic force; that it is a coincidence that this record has two originals by each of the three veterans in the band. “We play the best songs that are brought to the sessions; it could be six songs by one of us. It just so happens that the best originals brought to this session were two each by three of us.”

The fourth track is “Teo” by Thelonious Monk, one of two covers on this record. Often, Monk covers, no matter how well done, disrupt a contemporary jazz album because the music is so unique - they stand alone on the record like a flare. However, on this record “Teo” blends seamlessly. It is a testament to the strength of the original composition as well as to the manner in which this version is played. It swings tightly along with the rest of the album.

Marsalis describes the pace of the recording sessions: “One of the unique things about this album is how well we played from the first track. I don’t think we had to play more than two takes of any of the songs… we were so hooked up with each other. I think this is the first time we’ve done a record and it just showed up.”

Continues Marsalis: “We were so tight that if we’d wanted to we could have gone old-school and finished this whole record on the first day. We could have finished it by midnight. That’s how they used to do things at, for instance, Blue Note Records. But our thing is different. The tunes on this record are very difficult, but we are tight enough to make them sound easy. The difference is that we are a working band. Justin worked with us on the road for two and a half years before we made our first recording with him. At Blue Note, they knew ahead of time that they only had one day to make a record so the songs they brought in were simple blues, rhythm changes, and forms that were easily understood. So the records were like glorified jam sessions.”

After “Teo” comes a Marsalis original titled “Whiplash” that features a long section in which Calderazzo lays out and the piano-less trio expresses a robust, jumping, hopping stretch. Then Marsalis lays out, Calderazzo enters, and once again you can hear the piano and drums talking to each other, with the bass forming a spine for the two percussive instruments to dance around. It is a stunning trio performance that ends with Marsalis re-entering for one phrase of melody, then a transfixing, melodic solo by Faulkner.

“As Summer into Autumn Slips,” a long, airy ballad by Calderazzo, follows. “There’s an openness to this ballad and our performance,” says Calderazzo, “that is something we enjoy, that we haven’t done much of so far. It might be an avenue for us to explore more in the future.” The tune is daringly open. A permeating, hypnotic three-note phrase by Revis on bass sews together the atmospheric improvisations of Calderazzo and Marsalis and the soft mallets and cymbals of Faulkner. Slowly the looseness coalesces and tightens into crescendo, before settling back down softly.

The album closes with a stunning sequence of two songs, both with Marsalis on tenor saxophone - an original by Marsalis, “Endymion,” and a 1930 standard “My Ideal,” by Robin, Chase, and Whiting. What is so extraordinary about this coupling relates to how Marsalis describes the “jam session” quality of many single-day recording sessions in the so-called “golden years” of jazz. “My Ideal” might have been one of the standards brought to one of those types of recording sessions and it would be a mere vehicle for blowing. Yet, here, Marsalis closes this record - an extraordinary showcase for the state of this quartet’s art - with this standard, and it forms an unlikely beautiful coupling with “Endymion,” a challenging, raucous original. Perhaps a connective tissue comes from the use of major thirds in both performances. In “My Ideal,” you can hear everybody who ever played this tune – among others, Ben Webster, Chet Baker, and especially Sonny Rollins.

The recording sessions, which were covered by Sam Stephenson for the Paris Review, got off to a fast start. The band was hungry to record. Said Marsalis afterward:

“This is the first record that happened this fast. It just clicked – bam, bam. It had never happened quite like that for us. On the first day we began at two o’clock and by six o’clock we had three songs in the can.”

Revis concurs: “Everything flowed. There has always been implicit trust in this band but for some reason with this session it just flowed so easily.”

Marsalis says of his bandmates: “I feel blessed to have marvelously talented musicians in this band that can play very difficult tunes and hook them up and make it sound easy. This recording is a perfect example. They always hook it up.”

In twenty years, we may look back on this record as marking the beginning of a new prime for the Branford Marsalis Quartet.