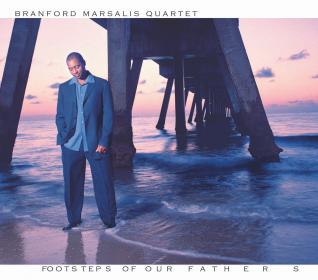

Branford Marsalis has never been one to stand still. The acclaimed saxophonist forges new paths with an assurance born of lifelong dedication and keenly honed knowledge, in the company of his stunning quartet. Together they have created Footsteps of Our Fathers, a joyous homage to jazz immortals living and dead who helped shape a value system that inspires not only Branford’s playing and writing, but also his determination to ensure that true creativity will be properly documented through his new Marsalis Music label.

“I’ve always been an advocate of expanding modern concepts in jazz,” Branford says of his new album, “but I’ve felt this was best done through the tradition. When my brother Wynton and I came to New York 20 years ago and unabashedly admitted that we were influenced by people like Miles Davis, I was shocked that we were criticized and called “neoclassicists”. But I continued to do what I was doing, and waited to see if the muse would be kind enough to let me expand the tradition. This was the way I thought it should be done, from talking to people like Dizzy Gillespie and Herbie Hancock.”

Branford’s experiences as a teacher, most recently at San Francisco State, have only reconfirmed these feelings. “A lot of young musicians today are more impressed with instrumentalism than with musicianship,” he notes. “They idolize amazing players, but don’t pay attention to the music. Since my own playing has matured in the last few years, and since my band now has its own sound, it struck me as the perfect time to make Footsteps of our Fathers and stress the need for a more thorough knowledge of the tradition.”

Few will doubt that Branford and his quartet, featuring pianist Joey Calderazzo, bassist Eric Revis, and drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts, are ready for such a challenge. Their previous recording, Contemporary Jazz, received the 2000 Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Jazz Album. Where that disc focused primarily on original compositions, Footsteps of Our Fathers revisits four masterpieces from the years 1955-1964, a particularly rich decade of recorded jazz.

The album opens with “Giggin’,” a typically idiosyncratic blues line that alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman recorded in 1959 with trumpeter Don Cherry, bassist Percy Heath and drummer Shelly Manne. “Ornette Coleman is just one of the great geniuses of the music,” Branford explains, “and `Giggin” is one of his earlier songs, so it still has a real bebop flair. I thought it would be great to play one of his pianoless quartet songs with a piano, and it took me a while to figure out how to do it. The best way is to have the piano take the place of the trumpet, although I ended up having Joey play Ornette’s saxophone lines while I play the trumpet lines on soprano sax. Then Joey plays his solo with just the right hand.”

Calderazzo lays out on “The Freedom Suite,” the 1958 call for an end to racial discrimination that Sonny Rollins created with bassist Oscar Pettiford and drummer Max Roach. “Sonny is one of my all-time favorites, probably the greatest improviser I ever heard – and that includes Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker,” Branford asserts. “You get the impression that he can play anything he’s ever heard at any moment – his data base is unreal. Sonny helped me a lot with rhythm, those crazy ideas that he has bouncing around, yet he tends to be underappreciated by a lot of saxophone players who put all of their effort into emulating John Coltrane. I’ve been fortunate to dig both Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, and to look upon them as equal influences. I’ve always loved `The Freedom Suite’ and loved playing trio, and there was a time when I would play one movement or another during our concerts, just to get it under my belt. Normally, we’re not going to do that much trio music with the quartet, but Footsteps of Our Fathers was the perfect time to do it.”

John Coltrane, the other tenor titan acknowledged here, created “A Love Supreme” in 1964 with his classic quartet of pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones. This four-part suite became Coltrane’s most popular composition, and was recorded by a previous edition of Branford’s quartet in 1991 for the AIDS Awareness anthology Stolen Moments: Red Hot + Cool. “I wasn’t really ready to play `A Love Supreme’ then;” Branford admits; “but the only way to get at a piece like that is to keep playing it, because you’re not going to get it right the first time. So I’ve worked on it, and my playing has come a long way since ‘91. The band is in a space where we can approximate the emotional impact that Trane’s band had.”

To complete the ambitious program, Branford chose “Concorde,” which pianist John Lewis composed for the 1955 Modern Jazz Quartet recording on which drummer Connie Kay first joined original MJQ members Lewis, vibist Milt Jackson, and bassist Percy Heath. “The genius of what the Modern Jazz Quartet did is so subtle, not in-your-face like what John Coltrane did,” Branford emphasizes, “and `Concorde’ is our way of saying thank you. John Lewis wrote songs that were technically demanding for each musician in the band, yet still required that everyone work in a group context. You have to really be in the moment to make his music work. We extended the performance compared to the original MJQ recording by finding the natural points of expansion. Where the MJQ didn’t go into straight swing until Milt Jackson’s final solo, for instance, I wanted more of a raucous, Duke Ellington thing. And Tain knows all about [Ellington drummer] Sonny Greer. The performance just builds and builds, then explodes.”

From beginning to end, Footsteps of Our Fathers displays a focus and sustained interaction that has marked all of Branford’s recent music. “We get better every time,” he says of his quartet with pride. “It’s unbelievable the way the band has grown. We’re all serious about playing, not like when we were younger and more interested in having fun. That’s why, when I was in my twenties, I could join Sting’s band or The Tonight Show and not really play for a year or more. I can’t see that happening again in my future, though. No more elegant diversions, because I don’t want to spend that much time not playing.”

This degree of dedication has been reinforced by the creation of Marsalis Music, an independent label distributed by another artist-based company, Rounder Records. The decision to launch such a label means even more from an artist who has enjoyed a number of high-profile gigs that jazz musicians rarely obtain. “I realized that what I really wanted to do was play during my years on The Tonight Show,” Branford says. “Really creative musical guests would come on – people like Marcus Roberts, Bruce Hornsby, Sting, Marilyn Horne, Kathleen Battle, Wynton, and Placido Domingo – and remind me of what I wasn’t doing. The irony of the situation really hit home. It wasn’t that I regretted that gig, or playing with Sting. Both experiences were a lot of fun, but I saw that I couldn’t devote that much time to something else at the expense of my own music. You can’t develop your conception on Saturday and Sunday. Great musicians and great bands go on the road, they tour and discover their own thing.”

In the case of Branford Marsalis, they also create a new record label to foster such independent spirits. “My brother Ellis, who works in computers and doesn’t play music, told me once that he had what he called a `philosophical conflict’ at his job. He was bothered by the clash between people like himself, who want to provide a service to the community and make a profit, and those who just want to make a profit at the expense of the community. I never forgot that insight, and it describes perfectly what Marsalis Music will be about. We want to provide a service to the music community first. We want to create an atmosphere where people who make creative music can be heard.”

Footsteps of Our Fathers is the first, glorious step on that path.