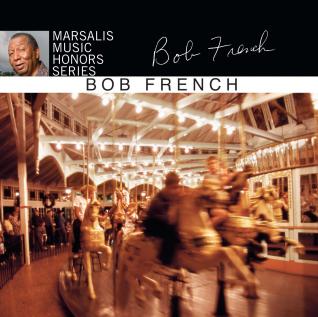

New Orleans has been a primary source of musical creativity for more than a century, and the Tuxedo Band has been at the center of New Orleans music most of the way. “The Tuxedo Band began as an orchestra, either in 1909 or 1910, depending on where you get your information,” notes Bob French, who has had charge of the incredible Tuxedo legacy for the last 30 years. A multi-generational celebration of traditional New Orleans music is French’s focus in a new volume of the Marsalis Music label’s Honors Series.

Bob French considers the Crescent City’s musical legacy with an ensemble that includes French’s contemporary Bill Huntington, emerging brass stars Kid Chocolate and Trombone Shorty, and young veterans Branford Marsalis, Harry Connick, Jr., Chris Severin and Ellen Smith. Each is a longtime acquaintance and playing partner of the drummer who represents one of the storied jazz families of New Orleans.

“My grandfather Robert was a tuba player,” French notes, “and I had a great uncle Maurice who played trombone with Louis Armstrong. Others on my Dad’s side were gospel singers, and my Dad, Albert “Papa” French, played guitar and banjo until he eventually put the guitar under the bed. He played in the Tuxedo Band, and became the third leader in 1956, after the founder Oscar “Papa” Celestin and his successor Eddie Pierson. I took over after my Dad in 1977.”

As a child, Bob French was determined to become a drummer, despite his father’s warning. “‘Drummer’s are the first ones on the gig, and the last to leave,’ is what he told me, and in 1951 he bought me a brand new King trumpet. It might have been good for me, but I didn’t want to be a trumpeter. So I started taking lessons from Louis Barbarin, Paul’s relative and to my mind a better drummer, and my Dad bought me a second-hand set. Within two or three years, I was playing gigs.”

Like most of his peers, French got his professional start playing rhythm and blues. “New Orleans musicians are smarter than others around the country,” he explains. “If you can make some money playing a style of music, you play it. Even on R&B gigs, we would start with things like ‘Satin Doll.’ I organized a band in high school that included James Booker and Art and Charles Neville, and Kidd Jordan and Alvin Batiste also played in my R&B band. After Earl Palmer left for California, I began playing and recording with Dave Bartholomew, who’s a relative on my mother’s side. I got a call one morning when Fats Domino’s drummer didn’t show up, and after that Fats told Dave to ‘Hire that boy for all of

my recordings.’ Fats wanted to take me on the road, too, but Dave said, ‘Don’t do it. He’ll pay you $400 per week and give you $2000 worth of trouble.’”

One style that initially held no appeal for the young drummer was the music that his father was playing with the Tuxedo Band. “I had been around the traditional music in my parents’ home, but I thought it was corny,” French admits. “Then one night, when Louis Barbarin got sick, my Dad came into my room and said, ‘Put on your blue suit, you’re playing with us tonight.’ Talk about a rude awakening! ‘Bourbon Street Parade’ was the only thing I knew; but I went on the gig, and all of those great musicians – [pianist] Jeanette Kimball, [bassist] Frank Fields, [trombonist] Frog Joseph – started laughing when they saw me, because they knew that I didn’t know the music. I scuffled the whole night and was embarrassed, so from that night on I made it a point to learn the music.”

French learned the music so well that he became one of its living legends. Through leading the Tuxedo Band since 1977, and through the popular radio shifts he holds down each Tuesday and Friday mornings on New Orleans community non-profit station WWOZ (which streams at www.wwoz.org), he has brought the music he loves to countless numbers of people. He has also become a colleague to scores of New Orleans players and singers from several generations. The seven associates he features on Bob French are indicative of the range of artists who he has touched. “[Bassist] Chris Severin and [vocalist] Ellen Smith are part of my regular band. Chocolate [trumpeter Leon “Kid Chocolate” Brown] used to be, too, and [banjo player] Bill Huntington worked with me when he lived in New Orleans. I met Chris when he was 15 and played a gig with Ellis Marsalis and me, and I brought Chocolate out when he was 16 or 17 and only knew a few tunes. I’ve known Trombone Shorty [trombonist Troy Andrews] all his life.

The ties between French and the two Marsalis Music artists featured on his disc are also extensive. “I first met Harry Connick, Jr. when he was six or seven, and he would come to my gig once a week and play one of the three or four tunes he knew. Betty Blanc was teaching him classical music, and James Booker was around his house every day, so he had the best of both worlds. Then Harry’s father wanted him to have a jazz teacher, so I gave him Ellis’ number and he had the best of all worlds. Harry asked me once how we put up with him when he was so little, and I told him it was because we knew he had talent. Unbeknownst to most people, he is one of the baddest piano players in the world. And he doesn’t carry himself like a big star. For those of us who knew him in New Orleans, he hasn’t changed a bit.

“Now Branford, I’ve known him since before he was born. I went to school with his mother, and played gigs with his father from early on. He and his brother Wynton showed up to play on one of my gigs with Ellis when they were about 13 and 12 years old. They played two tunes and got the hell off – Ellis was laughing like crazy. I was so happy at the session because of how great Branford played.”

Beyond the attention he paid to selecting the personnel, French also applied great care in assembling the program. “I gave the session some thought,” he explains, “because you have to choose how far back to go, what moods you want to set, things like that. I tried to set it up as ‘one up, one down,’ because you can’t play everything fast or you’ll kill the band. I wanted to include music that people could relate to New Orleans, which is why ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’ is included. As a rule, I don’t do ‘The Saints,’ after playing it on Bourbon Street six times a night, six nights a week, but people relate to it. We had to do ‘Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans’ because I have friends who are still scattered all over the United States. George Lewis’ ‘Burgundy Street Blues’ is there, because you would not believe how popular George’s music remains all over the world. And ‘You are My Sunshine,’ which was written by Louisiana Governor Jimmy Davis, well that’s the hit,” he laughs. “Ellen Smith and I went to Europe after the recording, to play with Sammy Rivington and other great European musicians, and they all knew the words when I asked them to come in on the verse. My yodeling really went over well in Switzerland.”

While there are plenty of such upbeat moments on Bob French, there are also such introspective highlights as “Just a Closer Walk with Thee,” as might be expected from a man who lost his home to the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. “We could have subtitled the album ‘New Orleans Devastated,” he remarks; ‘but the most important thing I wanted to relate is the importance for the youngsters who are coming behind me, and the ones behind them, to learn this music and start playing it. Not playing it like me, but like them. If people get nothing else out of the album, I hope it leads some of the youngsters to pay attention to the real New Orleans music.”

Marsalis Music Honors Bob French, together with Marsalis Music Honors Alvin Batiste, is being released on April 10, 2007.