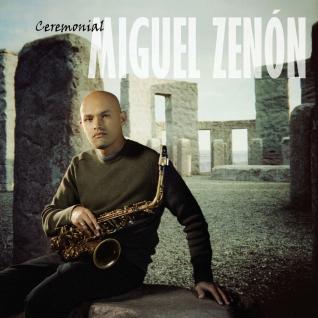

At its best, the most passionate and promising of today’s jazz is less a fusion of exotic and mainstream elements than a reflection of the more complex, cosmopolitan environment of the contemporary improvising musician. Miguel Zenón whose alto saxophone and quartet make their Marsalis Music debut on Ceremonial, is a stellar example of the blends of energy, passion, intellect and spirit that ensures the music’s continued relevance and growth.

“The main concept of the recording,” Zenón explains, “is going for something melodic, with the Latin influences melted into the jazz world, rather than just trying things to show that I can play a lot of notes fast. In my opinion, you can get to people in two ways when you play music. You can either be really flashy, or so intense that the energy takes you, even if the sound is quiet or the tempo is slow. That is the kind of quality I want in my music, that subliminal thing that takes you without hitting you in the face.”

Zenón was born and raised in the Santurce section of San Juan, Puerto Rico, and has played music since the age of 10. “There was an old guy in the project where I lived with my family who would give free music lessons if you passed his test, and I sought him out,” he recalls. “He taught me to read, solfeggio, those kinds of things. We had already been given recorders in elementary school, and when my music teacher at school heard how much I had learned, he suggested that I apply to Escuela Libre de Música, San Juan’s arts high school.”

While Zenón originally planned to continue concentrating on a career as an engineer, the six years he spent studying saxophone with Angel Marrero at Escuela Libre left the young musician well-grounded in basic techniques, and by the 11th grade Zenón had discovered jazz. “I started buying a few records – some Bird, some Tito Puente – and getting into it; but there was no jazz training at the school, so I had to learn jazz harmony by ear.” A year later, torn between his continued interest in engineering and the growing musical passion fueled by a small group of his hometown peers, Zenón was at a crossroads. “There was only so much you could learn, and only so many records we could obtain back then. Berklee College had accepted me, but my family couldn’t afford the tuition. Finally, I decided to stay in Puerto Rico and study music at home.” A year later, in the spring of 1995, when Berklee sent faculty to Puerto Rico to conduct its first workshops and award its first scholarships on the island, Zenón received one of the awards, which allowed him to enroll in Boston’s famed jazz college.

Berklee is where Zenón received his first specific jazz instruction, and where he was thrust into a world of young musicians with the same kind of hunger he already possessed. Soon he was in the thick of Boston’s creative scene. “After a year, I started playing with Bob Moses and the Either/Orchestra,” he recalls, “and I met Danilo Pérez, who introduced me to so many established musicians. I had wanted to emulate many of my favorite musicians at first; but after getting in touch with older musicians like Danilo and Bob Moses, I realized how important it is for people to relate to something that represents you.”

Encouraged by Pérez, Zenón moved to New York in 1998, and began studying for a Master’s Degree at the Manhattan School of Music. Soon he was hanging out with fellow Puerto Rican (and fellow Angel Marrero student) David Sánchez, sitting in on a few tunes at Sánchez’s quintet gigs, and rehearsing the new music that Sánchez was writing to feature two saxophones. At the 1999-2000 Orvieto Jazz Festival, Zenón became a permanent member of what was now the David Sánchez Sextet. “I also worked with the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra, Guillermo Klein, Ray Barretto and William Cepeda, who inspired me to do more research on the music of Puerto Rico. I left school for a while to do some of these different things, but went back and got my Master’s in 2001.”

When Zenón’s original compositions, first heard on David Sánchez’s albums Melaza and Travesía, became more of a focal point, the alto saxophonist assembled his own quartet featuring pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Hans Glawischnig and drummer Antonio Sánchez. “We started playing at the Jazz Gallery in New York, which is where we really developed our sound,” Zenón explains. “I was ready to record, and at the time the Fresh Sound New Talent label in Spain was the only company willing to let me document the music I wanted to play.” The resulting album, recorded in August 2001 and released as Looking Forward, was widely hailed, earning a place on the New York Times “alternative” list of the 10 best albums of 2002.

Even before that triumph, Zenón had made a major fan of Branford Marsalis, who had grown familiar with the young saxophonist’s music while producing David Sánchez’s discs. “A few days before the Fresh Sounds session, I went to hear Branford’s quartet play in Bryant Park,” Zenón explains. “When I went backstage to say hello, Branford said he was thinking of starting his own label and wanted to record me. I sent him the first record when it was done, and by then he had launched Marsalis Music. Then I found out he hadn’t just been talking.”

Ceremonial, which Branford produced, is a perfect realization of Zenón’s goals as both player and composer. “I definitely was trying to represent the worlds of jazz and Latin music equally, instead of creating music that leans one way or another, which happens too often with all kinds of fusions. I wanted the music seen as jazz music, and I wanted it to reflect all of my interests. By the end of my time in Boston, I had started listening to a lot of other music, and coming up with these other ideas. Then moving to New York was a real eye-opener, because I heard so many other kinds of music, and began to seriously study classical composers of the 20th century like Stravinsky, Charles Ives and Debussy. I also realized that things like science and mathematics, if used in the right way, can be applied to music.” Zenón and his band had just completed a European tour when they recorded Ceremonial in March 2003, and their empathy could not be clearer. “People always ask who my dream band would be,” he says with obvious pride. “Well, the musicians who play with me now are my dream band. The music I write is for them.” The core group expands to include vocalist Luciana Souza on “Transfiguration” and percussionist Hector “Tito” Matos on “Mega” and “440”. The seven original compositions Zenón created for the disc are framed by Silvio Rodriguez’s “Leyenda” and the traditional hymn “Great is Thy Faithfulness”, and every track reflects a seriousness of purpose that can be called spiritual without affectation. “I’m a very religious guy,” Zenón confirms. “My spiritual side is the most important thing. I believe that making music is what I was put here to do, to express my feelings and my view of life.”

2004 will be the year in which Miguel Zenón makes his mark. Shortly after the release of Ceremonial, he will participate in the inaugural season of the SF Modern Jazz Collective, an all-star octet led by Joshua Redman that also includes Bobby Hutcherson, Nicholas Payton, Josh Roseman, Renee Rosnes, Robert Hurst and Brian Blade that will debut in San Francisco and tour throughout the state of California in March. By then, Ceremonial should have listeners everywhere abuzz over Zenón’s bold, beautiful music.