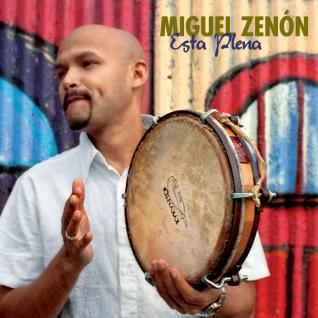

Earthy and sophisticated, the music of Esta Plena suggests a summing up of the work of saxophonist and composer Miguel Zenón thus far. It is rooted in the traditional plena music of Zenón’s native Puerto Rico – reinterpreted with the sensibility, the approach and the tools of 21st century jazz.

Zenón’s first new work since receiving both a MacArthur and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 – the first time a jazz musician has been awarded both on a single calendar year – Esta Plena is the direct result of the Guggenheim Fellowship, awarded to him for musical composition. Also called the “genius grant,” the no-strings-attached MacArthur Fellowship recognized Zenón for “drawing from a variety of jazz idioms and the music of his native Puerto Rico to create complex, accessible sounds that overflow with emotion.”

Esta Plena could be viewed as a follow-up of sorts to Jíbaro, Zenón’s brilliant 2005 reworking of the country music of Puerto Rico. “It is definitely connected to the idea behind Jíbaro, in that we took something that was very folkloric and put it in a jazz context,” says Zenón, “but on this record we went a step further by incorporating some of the actual instruments used in the music which are so central to this style. Because of the Guggenheim, I was able to do more extensive research, go deeper than I had for Jíbaro.

“Initially, what drove these projects was a personal desire to know more about my own culture,” he says. “After I left Puerto Rico, I immersed myself in jazz for a very long time so I wasn’t really dealing with Puerto Rican music. I had been exposed to it growing up, but it wasn’t until I began writing my own music that I really started to pay close attention to it. That’s when I decided to explore this music and find out more about my roots, who I really am, where I came from… and I felt it was important to study it at a very fundamental, core level. That’s how these projects were born.”

In his liner notes, Zenón defines plena as “a by-product of Spanish Colonization, combining African rhythmic syncopations with European harmonies and melodic cadences.” Moreover, since its emergence in the 19th century in Ponce, a city in the southern coast of Puerto Rico, plena has been the music of the disenfranchised while functioning as an oral newspaper. Singing to the rhythms of the panderos, or hand held hand-held drums, the pleneros, or plena singers, “described the events of everyday life as experienced by the impoverished classes of the Puerto Rican population,” explains Zenón. “These lyrics eventually expanded to include themes of patriotism, social protest, love, humor, and just plain appreciation for the plena and the pandero.”

He says that he approached Esta Plena as if bringing together two bands – his standard jazz quartet and a plena group – both going at once. It’s an idea that demands special, and committed, musicians, and Zenón has been able to work for the past five years with the same quartet comprised of Luis Perdomo, piano; Hans Glawischnig, bass; and Henry Cole, drums. Such consistency is a rarity in jazz.

“I’ve been so lucky to have the same group to work with all this time,” says Zenón. “When you play with people for so long you basically know how they play, how they are going to react and how they might bring their personalities to a tune. So after awhile, you are definitely writing for specific musicians, for how they are going to play it.”

In part as a nod to the tradition, in part as a way of enriching the overall sound of the project, half of the tracks in Esta Plena have lyrics and are sung. “At first, I was not going to write any lyrics,” says Zenón. “I had intended to write instrumental songs. But the more I listened to the music, the more I became interested in writing lyrics. I realized that this was very different from Jíbaro because jíbaro music is actually a big family of styles from different regions while plena has only one rhythm; there are no variations. So, I was trying to find different ways to use that rhythm and bring variety to the music. Adding lyrics helped me do that.”

To his surprise, Zenón found that, when writing the charts for Esta Plena, he “didn’t really feel that the saxophone was the focus of the music. It was all about the panderos – and everything was built around it,” he explains. “Of course, it’s my recording so I take solos, but when I wrote the music, everything came from those drums and that pattern that defines plena. The saxophone is there to add texture, especially in the songs with lyrics.”

As personal as it was for Zenón, musically, reclaiming music with deep folk roots also evokes a jazz tradition. Even beboppers, while creating some of the most complex and intellectually challenging popular music ever created, held on close to the blues, both as a reference and a place to connect with their audience.

“Having the folk roots gives the music a firm ground and gives me a lot of freedom to try a lot of things but still have that solid base,” says Zenón. “That folkloric root is so essential in music. It’s the purest music It’s not music played by trained musicians but music played by regular people.This is music from the people. This is music that can start a party anywhere. It’s simple and basic, and accessible, but at the same time, it’s so deep. That’s what we want to do with this record: try to keep the music out, in the street.”

For Zenón, Esta Plena represents not just another trip back home, but a rediscovery.